Why there is no “Real World” vs. “Scientific Numbers”

The problem of aggravating hunger in the world is one of the most recurring topics for every student of economics, environmental science etc. Most of the time, however, it is treated more as a grievous occurrence happening somewhere, and there is probably some NGO dealing with the matter already, right?

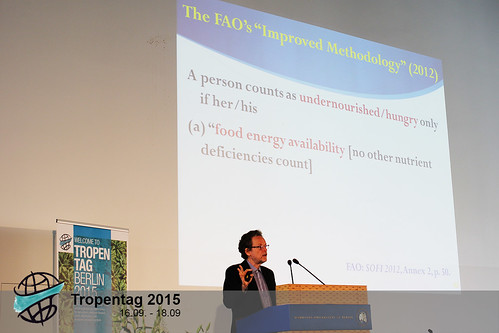

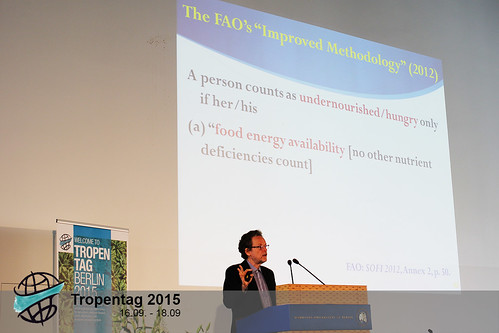

Thomas Pogge’s keynote opener on the first day of Tropentag did not, in fact, bring any insight into why a serious evaluation of the right to food is necessary or why it such an important moral imperative. What he did was shake up the conference room by delivering a smart critique on the statistics about hunger and hungry people that are divulged by what he considers “politically exposed organizations” such as the FAO and the World Bank. As we have covered already, his critique did not go without detractions but I still believed it to be a brilliant introduction to why we all are doing research and working in agriculture and food-related areas.

We as humankind should agree on compassion for those who suffer, especially when they suffer because they are in the wrong place at the wrong time. And once our consensus goes in the direction of ensuring our right to live and to thrive, then the questions of how to empower men and women sustainably and resiliently in food systems become relevant (video).

Pogge's focus has been on how information about hunger and undernourishment is constructed, handled and communicated and Brave Ndisale opened her presentation saying she was looking at the real people with real problems instead of numbers.

But I beg to differ: there is no “real world” versus “scientific numbers”. Instead, there are things that we as people recognize as problems and suffering, for which the research and the work scientists put into it in order to generate those numbers and help find a solution is a godsend. We need to have the numbers to know exactly who and where the enemy we are fighting is.

Thomas Pogge’s keynote opener on the first day of Tropentag did not, in fact, bring any insight into why a serious evaluation of the right to food is necessary or why it such an important moral imperative. What he did was shake up the conference room by delivering a smart critique on the statistics about hunger and hungry people that are divulged by what he considers “politically exposed organizations” such as the FAO and the World Bank. As we have covered already, his critique did not go without detractions but I still believed it to be a brilliant introduction to why we all are doing research and working in agriculture and food-related areas.

We as humankind should agree on compassion for those who suffer, especially when they suffer because they are in the wrong place at the wrong time. And once our consensus goes in the direction of ensuring our right to live and to thrive, then the questions of how to empower men and women sustainably and resiliently in food systems become relevant (video).

Pogge's focus has been on how information about hunger and undernourishment is constructed, handled and communicated and Brave Ndisale opened her presentation saying she was looking at the real people with real problems instead of numbers.

But I beg to differ: there is no “real world” versus “scientific numbers”. Instead, there are things that we as people recognize as problems and suffering, for which the research and the work scientists put into it in order to generate those numbers and help find a solution is a godsend. We need to have the numbers to know exactly who and where the enemy we are fighting is.

Thomas Pogge’s keynote opener on the first day of Tropentag did not, in fact, bring any insight into why a serious evaluation of the right to food is necessary or why it such an important moral imperative. What he did was shake up the conference room by delivering a smart critique on the statistics about hunger and hungry people that are divulged by what he considers “politically exposed organizations” such as the FAO and the World Bank. As we have covered already, his critique did not go without detractions but I still believed it to be a brilliant introduction to why we all are doing research and working in agriculture and food-related areas.

We as humankind should agree on compassion for those who suffer, especially when they suffer because they are in the wrong place at the wrong time. And once our consensus goes in the direction of ensuring our right to live and to thrive, then the questions of how to empower men and women sustainably and resiliently in food systems become relevant (video).

Pogge's focus has been on how information about hunger and undernourishment is constructed, handled and communicated and Brave Ndisale opened her presentation saying she was looking at the real people with real problems instead of numbers.

But I beg to differ: there is no “real world” versus “scientific numbers”. Instead, there are things that we as people recognize as problems and suffering, for which the research and the work scientists put into it in order to generate those numbers and help find a solution is a godsend. We need to have the numbers to know exactly who and where the enemy we are fighting is.

Thomas Pogge’s keynote opener on the first day of Tropentag did not, in fact, bring any insight into why a serious evaluation of the right to food is necessary or why it such an important moral imperative. What he did was shake up the conference room by delivering a smart critique on the statistics about hunger and hungry people that are divulged by what he considers “politically exposed organizations” such as the FAO and the World Bank. As we have covered already, his critique did not go without detractions but I still believed it to be a brilliant introduction to why we all are doing research and working in agriculture and food-related areas.

We as humankind should agree on compassion for those who suffer, especially when they suffer because they are in the wrong place at the wrong time. And once our consensus goes in the direction of ensuring our right to live and to thrive, then the questions of how to empower men and women sustainably and resiliently in food systems become relevant (video).

Pogge's focus has been on how information about hunger and undernourishment is constructed, handled and communicated and Brave Ndisale opened her presentation saying she was looking at the real people with real problems instead of numbers.

But I beg to differ: there is no “real world” versus “scientific numbers”. Instead, there are things that we as people recognize as problems and suffering, for which the research and the work scientists put into it in order to generate those numbers and help find a solution is a godsend. We need to have the numbers to know exactly who and where the enemy we are fighting is.

Comments

Post new comment